I Corinthians 1:18-24

I Corinthians 1:18-24

John 3:13-17

This fall, on the 500th anniversary of the reformation, we are revisiting history to ask what it might have to teach us about our faith and life today. And if we ask what issue is at the heart of the reformation– what was the biggest point of debate that divided the church – what would you say? What were you taught in history class? Often, the reformation is considered to be the result of the selling of indulgences.

The long road that led us to the sale of indulgences starts with a simple question: how do we heal our relationship with God when we have damaged it? Or, to use different language, what should we do when we realize that we have sinned? In Catholic tradition, which is our heritage as western Christians, we recover from sin in three steps: contrition, confession, and satisfaction. This is not so different from how many non-Catholics and even non-Christians understand the process of setting things right after doing something wrong. Contrition: First, we realize and regret that we’ve done something wrong. Confession: Then, we admit to God and others what we’ve done. Satisfaction: Finally, we attempt to “right the wrong,” either directly or indirectly. Contrition, confession, and satisfaction.

Indulgences are one way of solving the “satisfaction” part of the equation. If we feel badly about what we’ve done, we want to make up for it. And if we believe in hell or purgatory, as nearly all medieval Christians did, we want to avoid suffering in them. But what can we do to achieve satisfaction? And how will we know if we’ve done enough?

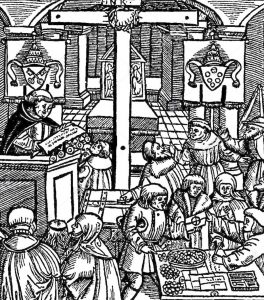

In response to these questions, the church developed a system to quantify how much satisfaction was required in each circumstance, and in what ways one could earn it. When people followed the church’s guidance, they received an indulgence, a promise of release from the punishment of sin, issued by a bishop or by the Pope. At first, indulgences were offered to those who had done something significant to make up for their sins: for example, going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, or building a cathedral, or fighting in a crusade.

Soon believers to begin to wonder: instead of going to all the trouble of a pilgrimage, a building project, or a war: couldn’t I just pay to make things right? As it turns out, the church had plenty of use for Christians’ money, and so the sale of indulgences began in the 12th century. It proved popular, and it grew. Then, as the papacy weakened, secular governments increasingly demanded a cut of the pie, too. Governments would only allow the sale of indulgences if they got as much as two-thirds of the sale returned to their own bank accounts. Guilt, it turned out, was profitable for many.

From the beginning, however, there were questions about indulgences. Something didn’t seem quite right about the church or the state benefiting financially. Then, you had to consider the needs of the poor — what about those who couldn’t afford to pay? And why should a bishop or a pope have the final say in where a person ended up after death? Martin Luther’s arguments on this topic were the ones that really caught fire. He wrote:

“Ask, for example: Why does not the pope liberate everyone from Purgatory for the sake of love (a most holy thing) and because of the supreme necessity of their souls? This would be morally the best of reasons. Meanwhile he redeems innumerable souls for money, a most perishable thing, with which to build St. Peter’s church, a very minor purpose.”

Ultimately, Luther came to believe not only that the sale of indulgences was a racket, but more importantly, that salvation is free. Contrition and confession are necessary in a life of faith, but not satisfaction. God’s forgiveness and grace is a gift we can never earn by through works or money. It is instead, against all logic, freely given.

It is because of the Reformation that at the beginning of worship in this community, when we have an opportunity to confess to God anything that we may have done against God or against God’s will for the world, we are immediately assured of God’s forgiveness –without any service or payment.

How could Luther be so sure? Why would God give us something so precious in return for so little? Can it really be possible that God is willing to reconcile with us after our most grievous sins, simply because we repent and confess them?

The texts we heard this morning, which are from the feast of the Holy Cross, speak to the disconnect between our human way of doing things and God’s way of doing things.

Paul says, “Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since… the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided… to save those who believe.”

And the writer of the Gospel of John proclaims, “Indeed, God did not send the Son in the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.”

God, thank goodness, does not approach things the same way a human court would. God is not waiting for us to balance the scales. God does not demand that we make up for our mistakes or suffer divine punishment. Instead, God recognizes that we cannot reach her by ourselves, whether through our understanding or through our merit. God wants to prevent us from suffering the pain of any distance from Godself. So, God does the unthinkable: forgive flawed people like us again, and again, and again. Without holding a grudge, without counting the cost, God forgives us, liberates us, saves us, out of love.

It seems to me that there is some self-satisfaction among Protestants when we discuss the medieval sale of indulgences. We’re so proud of what side of the argument our forebearers were on. We delight in the evidence of church corruption – and there was plenty of that. But just as Christian history is full of anti-semitism, bias against our parent religion, so Protestantism is often full of distain for Catholicism, our parent denomination. It’s as if we are teenagers, railing against our elders forever, never realizing how much we owe them, and how much they may still have to teach us.

For instance, although the sale of indulgences ended long ago, one could argue that here in America, a land whose ethos was shaped in large part by Protestants, we have set up a new moral system based on cash resources. The “protestant work ethic” values productivity above anything else. Therefore, there is an underlying instinct to distain those who cannot find a way to support themselves financially, whether that is the result of oppression, discrimination, health, or disability. As a society, we continue to show that we believe that the only people who really deserve housing, food, decent schooling, or reliable healthcare, are the ones who can pay for it. We fail to lift up the very Catholic idea of the sanctity and dignity of all life. In American in 2017, the simple phrase “Black Lives Matter” is still controversial.

Here is the strange good news, recorded in scripture and showing forth in human history: God is love. Love beyond measure, and love beyond wisdom. When we harm God’s creation, and God’s children, and God herself, God continues to love us. And God’s love is so expansive that it reaches towards us in all circumstances, bridging the gap between us and the holy one. God offers Manna, sends us Jesus, pours down her Spirit upon us. Our God so longs to be united with us, that she continues at all times to invite us to set aside every sin, accept her forgiveness, and choose a better way. How long has it been since you accepted that invitation fully?

Each of us has an invitation. It never runs out. And maybe, just maybe, if we accept that invitation, God’s love will transform us so deeply that we will begin to think and act just a little bit more like God. Maybe, if we spend more of our time abiding in God, our arrogance about human wisdom will fade away before the magnificence of God’s wisdom for our life together. Imagine what a world that would be. May it be so. Thanks be to God.