Jesus is teaching in Jerusalem. He is responding to question after question. People keep coming, the text tells us, to test him. They ask Jesus about taxes. They ask him about resurrection. They ask him about the commandments. In each case, Jesus responds wisely, revealing religious truth while sidestepping political land mines. Finally Jesus turns the tables, and begins to ask his own questions. What do you think about the Messiah? Whose son is he? How could he be the son of David, when David calls him Lord?

Suddenly the conversation dwindles. No one knows what to say. Everyone is afraid of getting it wrong, of looking like a fool. From that day on, the gospel writer tells us, no one dares to ask Jesus any more questions.

What a tragedy.

Reading the gospels, we learn that questions are essential if we want to learn about God. Much of Jesus’ teaching is in response to questions from the crowd. And when he is asked a question, he rarely gives a straight answer. Sometimes he tells a story. Most often, he asks a question in return. In our gospels, Jesus asks 307 questions. Questions are his favorite way of teaching.

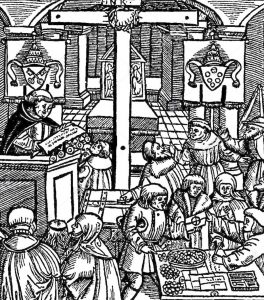

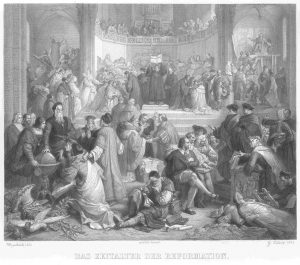

Today we mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. But that’s not quite right. The reformation was a complex social movement that lasted for hundreds of years and across many nations. What we’re marking today is the anniversary of the date when the German monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Cathedral. In this document, as you may know, Luther outlined his disagreements with the Roman Church’s teachings surrounding indulgences.

Interestingly, among Luther’s 95 theses, 8 are technically not “theses” at all. They are questions. Luther says, “The unbridled preaching of indulgences makes it difficult even for learned men to rescue the reverence which is due the pope from slander or from the shrewd questions of the laity.” and then he proceeds to list 8 shrewd questions, including this one: “Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love and the dire need of the souls that are there if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a church?”

Luther concludes his famous document by asserting that Christians must follow Christ at all costs, even if it means endangering themselves by going against the church. Nothing is more important, he says, than being honest about our beliefs and staying true to our conscience.

In the years since Luther’s actions, countless Christians have agreed with the idea that the church is in need of reform. We have questioned church teaching and practice. We have refused to endorse any teaching we do not believe to be true. We have separated from one another again, and again, and again, forming new movements and denominations to better embody our understanding of what it means to faithfully follow Christ.

The Protestant branches of the global Christian church which emerged from the Reformation have become known for our robust skepticism. The theologian Paul Tillich calls it the Protestant Principal. According to Tillich: “The heart of Protestantism asserts itself and says, “NO!” whenever a person, institution, or movement claims that its values are God’s values, its truth God’s truth, its action, God’s action.” In other words: no one ever gets it exactly right. Protestants are always looking for a way to improve.

The tradition we stand in as part of this congregation, the United Church of Christ, fully embraces this Protestant Principle. We claim among our ancestors of faith those pilgrims on the Mayflower who were willing to travel across an ocean to practice as they felt led. As they travelled, they carried with them these words: “I am verily persuaded the Lord hath more truth yet to break forth out of His Holy Word.”

In other words, our forebearers were clear that the Reformation will never be over. Why stop now? Our hearts, our churches, our communities, our nations are still marked by imperfection. In the UCC, we like to call ourselves “reformed and reforming.” It’s a process that never ends.

There is, of course, a danger in all of this. We could get too fascinated by our own clever questions and ideas and fail to honor the wisdom of others. We could get self-centered, and fail to work with others towards the Glory of God. I have concerns for our branch of the church in both of these areas. But when I have concerns, those concerns lead back to the same place. We are reformed, and we still need reforming.

Occasionally, when I meet with someone here at church, they hesitatingly reveal to me that they’re not so sure about this whole faith thing. I don’t know about Jesus, you tell me. I’m not certain about God. Other times, I hear questions you have about the church, because the church here or elsewhere has failed you, or because it mystifies you.

We may feel uncertain about sharing these kinds of questions with one another, or with God, but questions are never the problem. God is strong enough to withstand all of our questions. The church becomes better because our questions. Questions do not signal disrespect, or blasphemy. To ask a question is to show how much we long to really understand, and to more deeply trust in both God and our Christian community. Questions are a gift, in our individual journeys of faith, and in the journey of the church. Jesus loved questions.

So, I wonder: what questions do you have today? What questions do you have for God, or the church? How do you believe that we need to be reformed today: as individuals, or communities?

We read aloud the youth suggestions and came up with a few more:

- Why are we afraid to ask questions when that is how we learn?

- Let’s rejoice throughout the realm that You, Holy One, are still speaking. May all eyes be open to this.

- Why do some church leaders support flawed politicians for political agendas?

- How can we work toward being united with other Christian sects rather than being more separated?

- How can we speak and act with both power and humility?

- How can the church effectively spread dialogue and asking of questions to heal the rifts in our society?

- How long, O God, must we wait for good to overcome evil in our country, in all places rent by violence?

- O God, continue to show us your way through this wilderness time for our nation. Will we ever reach the “promised land” or will it always be just over the horizon?

- How can we help faith communities be instruments of connectedness rather than divisiveness (as they have too often been)?

- How do we confront racism effectively?

- May all remain open to the changes occurring in our own church

- We need more love and tolerance int he world. I ask why I was so fortunate to be born in this wonderful country with food, love, and safety at home while others were born in war torn areas without basic necessities.

- How can we be more effective in bridging the divisions that exist in our community and our world while simultaneously staying true to our own values and consciences?

- How do we really deal with poverty around the world?

- There is a need for a new reformation of the world, remembering that God loves us and that all people should believe in love and forgiveness! How can we in prayer ask God to reform the world?

- Loud protests — not just against, but in word and action, demonstrate what we are FOR.