This summer, as you know, we have been exploring songs of the Bible. And there is one extended song, taking up a whole book of the bible, that is quite different than anything else in our holy text. It is the song of Solomon, also known as the Song of Songs.

This summer, as you know, we have been exploring songs of the Bible. And there is one extended song, taking up a whole book of the bible, that is quite different than anything else in our holy text. It is the song of Solomon, also known as the Song of Songs.

You are unlikely to hear the Song of Solomon read very often in a church service. Depending on which schedule of bible readings a church follows, if it follows one at all, this book shows up either once in every three years, or never. One could argue that this is because the Song of Solomon does not once mention God, or God’s law, or God’s covenant. But I think it’s more likely that church leaders are uncomfortable with the contents of this book. There is a reason that I chose to preach on this text after our shared services with Tricon were over. There are passages in the Song of Solomon that I personally could not read in church without blushing. In fact, when I was at a Catholic retreat center earlier this summer, I learned that when a sister there received her first bible in the 1970s, she was strictly instructed never to read the Song of Solomon. Naturally, it was the very first thing that she looked up.

Traditionally, this text is attributed to the great King Solomon. However, most likely it was written later than he lived, around the 3rd century bce. No one knows quite why it was written, or where, or for whom. Biblical scholars have not been able to agree on a comprehensive structure or storyline for the entire book, either. It seems instead to be simply a collection, a set of passages, perhaps even a theatrical song cycle with the themes of love and longing.

Some of the less risqué passages from Song of Solomon have become well-known despite their absence in our Sunday scriptures. Descriptions of the bride in the song are often applied to Mary of Nazareth or Jesus: “a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys.” Some passages that we heard Barbara read are frequently used at weddings, including the recent royal wedding: “Arise my fair one and come away,” and “Set me as a seal upon your heart.” You may also have heard another beautiful line from this text at a wedding: “I am my beloved’s, and my beloved’s is mine.”

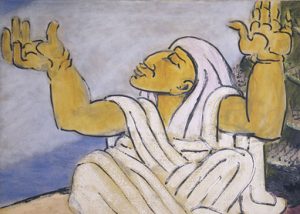

Passages and images from this text are popular with artists as well, from Marc Chagall to Toni Morrison to Madeline L’Engle. Even though the church doesn’t always make full use of it, our culture has.

If you read the text from beginning to end – as I imagine some of you will now, if you never have before – you may notice that the lovers spend a great deal of time complimenting one another. If anyone is looking for creative expressions for your modern day love declarations, you could seek out some resources here. When is the last time you told someone they were like a cluster of henna blossoms? Or you could wow them by comparing their teeth to a flock of shown ewes that have come up from the washing. Maybe even better, simply tell them that their love is better than wine.

In another famous section, the speaker says, “I am black and beautiful.” Due to centuries of racism, this text has often been translated, “I am black but beautiful.” Thankfully translators have corrected this in most modern versions, so that the text is again what it was originally meant to be: a celebration of dark-skinned beauty.

You may be wondering: why did this text end up in the Hebrew Scriptures? It helped that it was attributed to Solomon. But my guess is that mostly, the Song of Solomon made it into the canon because it was so popular. Song of Songs means: the best song. How could you make a book of the most important pieces of your cultural and religious inheritance without including the best love song ever written by your people?

There are many who would disagree with my interpretation, however. Both Jewish and Christian scholars have argued that there is nothing about human physical love in the text at all. No, they say, this text is only about the relationship between God and the people Israel; or Jesus, and the Church.

Mostly I find this interpretation laughable – really, read it through and see if you can agree with them. However, we can gain a few things if we open the door to a more theological interpretation of the text. If we apply this language to a relationship with God, it is striking in its intensity and intimacy. “I am my beloved’s, and my beloved’s is mine.” Or, “Love is stronger than death, passion fierce as the grave.” These are lovely ways to describe human spiritual fervor, and the depth and seriousness of God’s love for us.

Another argument in favor of the more theological interpretation comes from modern feminist and womanist theologians. If this is how God relates to the people Israel, or how Jesus relates to the church, or how the holy by whatever name relates to us individually; perhaps we are in a less lopsided power arrangement than we have traditionally imagined. The lovers in the text are mutually passionate and committed. Perhaps we also could be partners with God, sharing love with one another, and working together for the good of creation. (see Phyllis Trible, “Depatriarchalizing in the Biblical Interpretation,” among others).

Mostly, however, I find this text a gift because it does focus on human love. This is part of the human experience, and holiness can be found in it. Christian tradition holds so much that represses, denies, and shames the human body and human sexuality. One could even argue that our willful turning away from human physical experience has prevented us from providing moral leadership about good, mutual, safe, and loving physical touch.

Furthermore, in scriptures it is rare to find any description of love or marriage that is worth celebrating. Which biblical marriage or love affair would you care to duplicate in your own life? There aren’t many. Here, however, there is reciprocal delight and satisfaction: gifts from God, and worthy of celebration.

Please pray with me.

God, thank you for love of all kinds: 0ur love for you, your love for us, and our love for one another, in its many forms, in its great variety. May we seek out and celebrate love that honors us and honors all others, in all of our dignity, individuality, worth, and beauty. Amen.