WCUC member Rev. Polly Jenkins Man offered this sermon on October 18th.

Job 38:1-7, 34-41

Luke 15:25-32

Why Job? Why choose Job for my text today since the lectionary provides several good other choices, among them a psalm of praise, a letter of instruction, a discussion between Jesus and his disciples? Why settle on one of the most perplexing, challenging books of the Bible? The answer is that it’s more like Job chose me. Since my first class in a college biblical literature class, followed by Archibald McLeish ‘s play, J.B., and finally in a term paper on Job in theological school in which, with the supreme overconfidence of a fledgling seminarian, I tackled Carl Jung’s essay, Answer to Job, Job has intrigued me. So it seems that Job is not done with me.

The story of Job begins when Yahweh asks Satan, who has been wandering around the earth, “Have you considered my servant Job, a blameless and upright man who fears God and resists evil?

Satan replies, “Sure, I know Job. He’s rich, has a great family, a bunch of goats and lots of land. Why wouldn’t he be blameless and upright. He’s got it all. But…BUT…what if he had nothing, what if all that disappeared, what then? HA! HA! He’d curse you to your face.”

God accepts the challenge. “All right, Satan, do what you will; only do not let him die.” God makes a bet with Satan; that’s a fairly shocking thing for God to do. What are we to make of this God?

Job is then subjected to all manner of suffering and loss: his land, his animals, his gold, and finally, his whole family. Satan seems to do his worst. Over the course of time, four friends show up while Job sits on the dung-hill, scratching his sores with a pottery shard. These are his so-called comforters. Yet they do nothing of the sort.

Job, you must have done something wrong. Job, you musn’t question God. Job, don’t expect God to explain anything to you. Never is it, Job, “I see your suffering, I care for you.” There’s no sign of compassion or comfort.

Where is God all this time? The comforting, compassionate one. Absent, silent, simply a bystander? What are to make of this God? Who seems to be well aware of what’s going on, yet who is silent in the presence of suffering and does nothing? The eternal question…

The book of Job is most likely a variation of an ancient Near Eastern folk tale. The identity of the poet – and it surely was a poet who wrote this extraordinary verse – is lost to history. It’s not clear when or where the book was written, although it’s likely that the author was wrestling with Israel’s experiences of suffering, displacement and exile, wrestling with Yahweh over the timeless conundrum: the paradox of an all-knowing, all-loving benevolent being who permits human suffering.

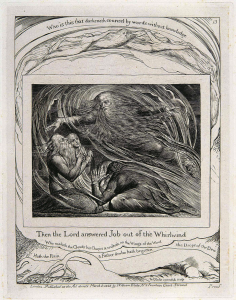

Given a loving Spirit, whom we believe God to be, we might expect that God would offer an apology, at the very least. Wouldn’t you expect God to do a better job than the comforters? I would. That’s not what happens, though, is it? Out of the whirlwind, God appears, storming, crashing through the wind and the clouds with a voice like a thunderclap:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding? Who determined its measurements? Surely you know! Can you lift up your voice to the clouds, can you send forth lightning?

It seems that God is mocking Job, making him feel even worse than he already does. It’s like God beating his chest. The Supreme Alpha Male! What are we to make of a God like this?

So begins God’s longest speech in the Bible with some of the most spectacular poetry, filled with all the wonder and diversity of God’s creation. I invite you to read those four chapters again or for the first time. It’s like God’s hymn of praise to the power and awe of God’s divine self.

But it’s not at all what Job was hoping for. Why does God need to prove anything to Job? What are we to make of a God like this?

Another story, one written much later, holds the seeds of an answer. Known as the parable of the prodigal son and also the parable of the older son. The younger brother, we remember, took his inheritance, moved far away from his family and squandered all of the money wastefully and irresponsibly. The other stayed home and did all the right things. A good son, an obedient son. Yet who gets the party? Not him, but his no-good younger brother.

When he complains, his father tells him; You are always with me and all that I have is yours, but your brother, he’s been lost, gone from my care, but now he’s home, he’s sorry and asks to be forgiven. That’s cause for rejoicing!

Job is like the son who stayed home. He always did the right things. But, God implies, that’s not the point. It’s not about what Job has done, it’s what he hasn’t done. Has he, like the elder son, ever acknowledged that all his blessings, all the good things of his life, are his by the grace of God?

Has Job doubted God’s existence, even for a moment? I know I have. Has he looked into his heart and seen that, like each and every one of us, he is far from perfect? I know I have.

Job, like the older brother in the parable, lived his life well: he was hard-working, faithful to family and community, respected by all. Perhaps Job took it for granted that he would have health and security. I know I have, too many times. Job probably worked hard to gain his wealth: but lots of people do. He was a loving husband and father; lots of people are and deserve to live well, but certainly not all do. Job was fortunate, he reaped the rewards of his labor but left out the part about thanking God. He led a good and a moral life. But it’s not about morality; its about love and wonder and awe of God.

Granted, the story of Job goes to extremes to make this point. At the same time, I find God’s answer to Job somewhat poignant. God pleading with a man to be loved just for who God is. That’s all. And that’s everything.

Love me, Job, not for all that I give you, but for who I am. I am who I am. I’m not a gambler, not a bystander, not a bully.

God is not some cosmic vending machine, dispensing blessings at the touch of a button; some gold today, a few goats tomorrow. The poet who gave us this work to ponder wrote long before the time of Jesus, yet I think it’s fair to say that God’s answer to Job anticipates the God we know as Jesus, who took on the business of human life in all its joys and all its sorrows, inviting us into his love, to love and follow him. It’s really not that complicated. God wants our love, always, continually, without qualification or condition, just because God is God, all knowing, all loving, all life-giving.

The poet Evi Seidman puts it this way:

I could never have thought of a pinecone,

or a porcupine or a pomegranate,

and even if I’ve thought of one,

how on earth would I have engineered a comet?

or organized life in a pond?

Where would I have found the energy

to make each snowflake different?

(It’s more like me to make one or two

passable models, build a mold and

crank ‘em out)

And it’s not like me at all to finish up

an entire mountain range, then go

back and carefully touch up, with tiny

forests of moss on the north side of

every stone.

I’ve got a pretty good head for details,

but it does seem likely that I’d have

left off the dots on a lady bug’s back.

I’d have neglected to tie in

each and every strand of silk

to every kernel of every ear of corn.

Why I love in house for two years

before I hung curtains in the bedroom.

-I’d probably never get around

to making a waterfall

And I can’t keep my mind on one thing

long enough to be a river

nor concentrate deeply enough

to become a deep cool spring.

And even if I had little boxes

of just the right atoms and molecules,

how long would it take me to assemble them

into even one drop of water?

And the shine that sparkles from that drop?

Why, I imagine I will spend the rest of forever

seeking the beginning of that Light.

You see? It’s a good thing I’m not in charge here.