This summer at WCUC we have been learning the stories of some of the earliest saints of the church. These are people who many of us have barely heard of. But without them, we would not be here: these are the folks who spread the word about Jesus, and helped to form a movement, and institutions, to bring that good news to us in 2014. We’ve talked about Phoebe, a deacon, and Junia, an apostle; Lydia, the first European Christian convert and a founder the church of Phillipi; and Clement of Rome, one of the first popes, who helped define the leadership and organization of the church.

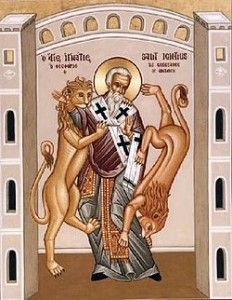

Today I want to spend a little time with Ignatius, a contemporary of Clement’s. This Ignatius is not the more famous one you may have heard of, Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, who lived in Spain in the 16th century. Our less famous Ignatius was instead a Bishop of Antioch (a city in modern Turkey) at the end of the first century of the common era.

Ignatius is known as one of the disciples of St. John. One tradition also names him as one of the children whom Jesus took into his arms and blessed. But we know almost nothing about his life or leadership in Antioch. His fame comes from the very end of his life. During the reign of the Emperor Trajan, Ignatius was arrested for his profession of Christianity and taken to Rome under guard of ten soldiers. On the way to his trial he composed a series of letters to the leaders of the Christian churches he was passing by. These letters are treasured for what they tell us about the church at the beginning of the second century, both in terms of theology and in terms of episcopacy, or church organization and leadership.

It is presumed that Ignatius’ famous journey ended in his execution. According to legend, he was sentenced to death in the Colosseum. Like many early Christians, Ignatius seemed to embrace the possibility of martyrdom as an opportunity to come closer to Christ, closer to God. His most famous quotation comes from his letter to the Romans. He says:

I am writing to all the Churches and I enjoin all, that I am dying willingly for God’s sake, if only you do not prevent it. I beg you, do not do me an untimely kindness. Allow me to be eaten by the beasts, which are my way of reaching to God. I am God’s wheat, and I am to be ground by the teeth of wild beasts, so that I may become the pure bread of Christ.

I’ll speak a little more about the traditions surrounding martyrdom in the early church when we meet again in August. But what did Ignatius write in those precious letters, before his death, those letters that were so treasured by the early church?

Ignatius spoke about Jesus, warning against any theology that denied Jesus’ human, physical life and disconnected him from history. He believed that Jesus was both human and divine; a point that had not yet been settled in Christian theology.

He spoke about the organization of the church, promoting the role of a single local Bishop to maintain unity and order and orthodoxy, and supervise the sacraments of marriage and eucharist, or communion. He was, of course, himself a bishop, and took that role very seriously, naming himself a God-bearer, in Greek, Theophoros.

But what has really caught my attention about Ignatius is that he was the first person to use the word “catholic” to describe the church: katholikos, the Greek word meaning “universal”, “complete,” and “whole.” He wrote: “wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the catholic Church.” He’s not talking about catholic with a capital “C”, as we do today, to differentiate between branches of the church, Catholic and Protestant and Orothodox. He’s using it in the same way it is used in the Nicene Creed: “We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic church”: one united, universal church.

Ignatius articulates a belief that all people following in the way of Jesus are united. This is a profound idea, given the way that the Christian movement was developing. The church was very diffuse and diverse. Apostles had travelled and founded churches far and wide, each taking their own version of Christian theology with them, each making their own decisions as to how to live out the way of Jesus. There was no central accountability; there was not even very good communication.

But Ignatius says: “wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the catholic Church.” He sought to promote Christian unity through a hierarchical bishop system which may not sound appealing to our congregational ears. But his goal was much bigger: unity among all Christians, in governance, yes, but also in theology and sacrament, and ultimately, in Christ.

I can only imagine how distressing it would be for Ignatius to discover what has happened to the church in our day; we are so divided: in governance, in theology, and in sacraments. And I wonder what our role is in responding to that division, as members of the United Church of Christ.

You may know that our denomination was born out of the ecumenical movement of the 20th century; a high tide of hope amongst denominations that we could begin to come together as a church. We in the UCC represent the unification of four separate denominations and many independent congregations (such as West Concord Union Church), into one church. One of our mottos is: United and Uniting.

Today the impulse for churches to come together comes from different motivations. The end of Christendom, the shrinking membership numbers and budgets of denominations are forcing us to wonder what it is we can share with each other. And as our conference minister, Jim Antal, would remind us, the environmental crisis also calls us urgently together in a prophetic role.

How can we, as individuals and congregations, and as a denomination, begin to embody the dream of unity that was shared by Ignatius, and Clement, and Paul, and so many others?

Bind us together, Lord. Give us the courage and humility to become one: in body, in spirit, in Christ.

May we serve you and your creation faithfully, one holy catholic church. Amen.