At the end of the book of Deuteronomy, Moses and the Israelites are nearing the goal of their long journey up out of slavery in Egypt. They are on the brink of the promised land. And then God says to Moses: “Your time to die is near… Soon you will lay down with your ancestors.”

No one panics. Instead, plans are put into place. Joshua is commissioned to succeed Moses in leading the people. Moses finishes the work of recording God’s law. When everything has been completed, God sends Moses up onto Mount Nebo, where he can see the promised land of Canaan. It is on this mountain, God tells him, that he will die and be gathered to his kin.

When Moses goes up to die on Mount Nebo, he is one hundred and twenty years old. Our scriptures say that his sight is unimpaired and his vigor has not abated. The Israelites weep for Moses for thirty days; then they continue on their journey.

We could feel sorry for Moses. After all, his life’s goal is not realized. After forty years of leading his people through the wilderness, he never gets to feel the promised land under his feet. But Moses has a good life, and a good death.

A good life, and a good death. Moses is rescued as a baby from the threat of Pharoah. He is chosen to lead his people on a freedom quest. He sees God face to face. Moses lives for 120 years with great eyesight and full vigor. And then — God tells him when it is time to die, and where and how to do it. There is time to prepare, and then, quickly, it is all over. His people have the opportunity to grieve, and they move on with their lives, treasuring his memory.

Notice what is missing from this story. No one seems surprised or outraged that Moses’ time has come. There’s no hand wringing over the best thing to do for him. There’s no long decline, no doctor’s visits, no doctor’s bills. There aren’t any 911 calls, hospital stays, or nursing homes. Moses has a good life, and a good death. I don’t feel sorry for him.

When folks gathered last week in the parlor after worship to talk about the book “Being Mortal,” the room was packed and it was hard to get a word in edgewise. Everyone had something they wanted to share. Too many of us have watched a parent, a sibling, a spouse, a friend, experience a bad death. Too many of us are worried about our own deaths – about pain or senility or extraordinary measures. The goals of our medical system seem to be at odds with our best interests at the end of life.

Physician Atul Gawande’s book breaks this issue open. He helps us see the problem. He has more questions than answers. In this society that values independence, what happens when it is no longer possible? In a medical system set up to view disease and death as the enemy, how do we prioritize well-being over treatment?

I have still more questions. Why have we never learned how to talk to one another about death to begin with? Why don’t we accompany each other as we ponder the mysteries of mortality, and as we come closer to the time of death? How can we as people of faith draw on the strengths of our tradition to resist the fear and denial of aging and death that are so much a part of our culture?

This morning, Janet read a part of the second story of creation in Genesis. Here, in a story about our beginnings, is one way to think about our endings.

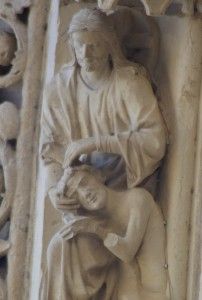

At the same time as God creates the earth and the heavens, God forms a human from the dust of the ground. God breathes into his nostrils the breath of life; and the human becomes a living being. This is what we are made out of: earth and breath.

And so, when time or tragedy ends our life, we return to where we came from. Our earth returns to the earth (dust to dust, ashes to ashes). Our breath, our spirit, returns to the breath and spirit of God. Death is often unwelcome, but it is the natural ending of every human life: a return to the very beginning; a return home.

There is a profound gentleness to this story from Genesis that gives me comfort. Imagine God using God’s own hands, to form the body of the human. Imagine God using God’s own breath to open up clay lungs. And God continues to care for that human, giving Adam a home, an earth and a garden to live in. God senses that it is not good for Adam to be alone and creates creature after creature to provide companionship, and finally, a full partner for him.

We were tenderly made of earth and breath, and we will return to where we came from. This is our faith’s understanding of eternal life. Not cosmetic surgery or cryogenics. Not desperate attempts to permanently preserve the kind of life we are living now. Through the eyes of faith, eternal life is something bigger, something more ancient, something more mysterious – the folding in of our lives into the source of all life.

We have been created by a God of compassion who accompanies us and awaits our homecoming. This knowledge can free us. It can free us to release those we love into God’s love. It can free us to live and age well, choosing quality of life over length of life, if we wish. It can free us to praise God in all circumstances, even on the threshold of death.

It is after he hears the news that he will die soon that Moses shares this song with the people:

Give ear, O heavens, and I will speak;

let the earth hear the words of my mouth.

May my teaching drop like the rain,

my speech condense like the dew;

like gentle rain on grass,

like showers on new growth.

For I will proclaim the name of the Lord;

ascribe greatness to our God!

Amen.